New Paintings

Clint Roenisch

April 4 - May 18, 2019

@

Clint Roenisch

190 St Helens Avenue

Toronto

We are pleased to present Dorian FitzGerald's fifth solo exhibition with the gallery. FitzGerald (b. 1975, lives Toronto) has spent the last ten years meticulously crafting a persuasive body of work revolving around a central tenet: that the follies, the deceptions, the indulgences, the grand edifices, the opulences, the waste, the vanities, the subterfuges and the chummy pacts of the wealthy and the powerful, are all fodder for scrutiny. In doing so, FitzGerald has been likened to a contemporary court painter, documenting - often on a monumental scale - these various lines of socio-political inquiry. In doing so, FitzGerald also knowingly underscores the conundrum at the root of his endeavours: that he is largely beholden to the very strata he is painting. His subject matter, therefore, has increasingly pointed towards issues of labour, craft and patronage. Canadian Art has written that in, “combining fractal-like forms with imagery celebrating opulence and luxury, FitzGerald’s paintings manifest a critically conceived parallel wealth that transcends the economic and experiential barriers that separate the super-rich from wider society.” FitzGerald’s method of working, often seated cross- legged directly on the canvas, requires infinite patience and a granular attention to detail that, taken together, suggest a kinship with Tibetan sand painting. While the latter, once finished, is soon wiped away to drive home the impermanence of all things, FitzGerald’s works tend to hold a mirror up to that innately human wish to be exalted and remembered in the minds of others before the scythe comes down, as it inevitably does for king, shepherd (and painter) alike. In doing so, FitzGerald has even called into question his own motives. Indeed, his previous exhibition was entitled Weltverbesserungssyndrom, which roughly translates as World Improvement Syndrome and can be interpreted as a kind of narcissistic personality disorder that masquerades as improving the situation of others - in this case delivering aesthetic and cerebral pleasure for the viewer - for the attention it brings to the doer. FitzGerald fully understands the paradox of using ostensibly beautiful works of art to deliver barbed comment on the very subjects he has so painstakingly rendered. Furthermore one wonders whether a kind of Stockholm syndrome sets in at some point (where the hostage falls in love with their kidnapper) since the largest paintings take years to finish and FitzGerald invests so much of himself in the preliminary research and their subsequent execution.

Works in the new exhibition include Crown For The King Of Adra, circa 1664. The crown was a gift from James Duke of York, as Governor of the Royal African Company to the king of Adra on the coast of Guinea that was meant to flatter him and and act as a diplomatic incentive to help the English facilitate their slave trade. In fact the crown (“just like our queen wears...”) was made of brass and the ‘diamonds’ were simply glass.

Aquarium (Taboo), at 128” long and 40” high, was two years in the making. The painting shows a vibrant aquatic scene, with dazzling exotic fish and a mesmerizing array of coral. But the fish are black market, the coral has been pilfered, the 240 gallon tank is overcrowded with 53 specimens and the entire enterprise is kept alive by a complex system that is wholly unnatural and requires constant vigilance to prevent collapse. Of course wild fish bound for the aquarium market must be caught alive and thus unsavoury divers prowl the reefs to find them and often use cyanide spray to stun them (or inadvertently kill them if too much is used). The cyanide, when it settles on coral, soon kills that too.

Malcolm Forbes’ Balloon, Château de Balleroy, Normandy, France depicts a massive hot-air balloon that Forbes had commissioned in the shape of his 17th century chateau, aloft on the lawn of same. Forbes, whose name became synonymous with modern wealth and jockeying for position, was known to brag that he owned more Faberge eggs than the Kremlin (12 to 10...) and was never shy of using his magazine’s motto, Capitalist Tool, on his 727 jet and his helicopter and his satin bowling jackets and once gave the mayor of Moscow a Capitalist Tool tote bag. He was also fond of telling people "I owe it all to hard work, initiative . . . and the death of my father.”

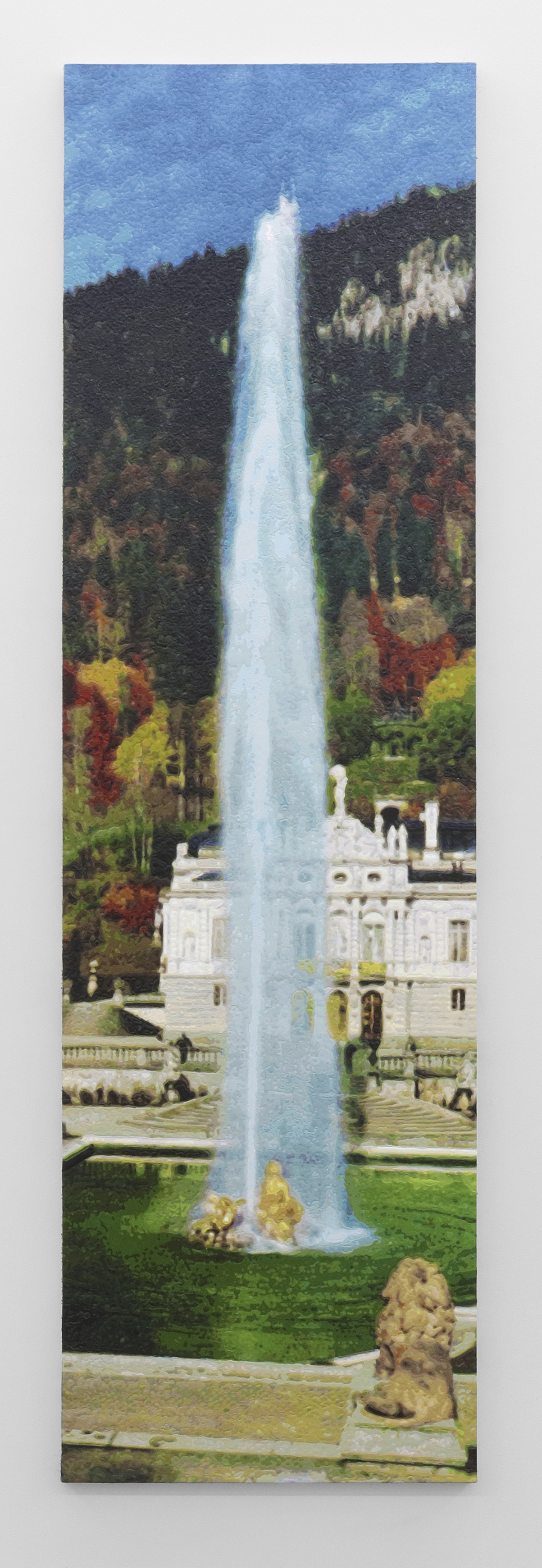

Fountain in Bavaria, Schloss Linderhof, for Ludwig II shows the comically ejaculatory fountain of Linderhof Castle, built by King Ludwig II. Born in 1845, Ludwig became Bavaria’s king at age 18 but was made politically irrelevant in 1871 when the various princes of the German states met in the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles to proclaim William I of Prussia as German Emperor. Now having time on his hands Ludwig plunged his kingdom into massive debt with megalomaniac construction projects like the Linderhof castle. He often disliked seeing his staff, so the dining table was built such that it could be set with food by the servants in the kitchen below and then winched up through the floor into the dining room, where Ludwig, sometimes dressed up as the French king Louis XIV, with whom he was obsessed, would sit down to eat alone. Eventually because of his reckless spending the German government decided to declare Ludwig insane and replace him with his uncle. On 12 June 1886, Ludwig was taken by force to be confined to a royal cell in the Berg palace on the shores of Lake Starnberg. His death the next day was never fully explained. Both Ludwig and his doctor were found drowned in the lake.

Iron Age Skull and Crown (Warrior or Druid), Kent, United Kingdom

The grave, dated to around 250 to 150 BC, contained the skeleton of a man in his thirties, short and slightly built. On the skull was a bronze headband, with the remains of another band that would have gone over the top. Both the skull and the "crown", as it came to be named, were badly damaged, thought by the archaeologists who discovered it to be the result of ploughing. Closer inspection after cleaning revealed it to be intricately decorated in the La Tène style, known to us as Celtic. Some historians have suggested that he was a druid, a member of the pre-Roman British intellectual and priestly class. Theirs was to serve as advisor to kings and chieftains, as judge, as teacher, and as a ritual leader and authority in matters of worship and ceremony. They were also philosophers, astronomers, and mathematicians and were in general the keepers of the knowledge store of the entire society. The bronze of the crown, now dull, its copper verdigris leaching into the side of the skull, would once have been burnished till it shone.

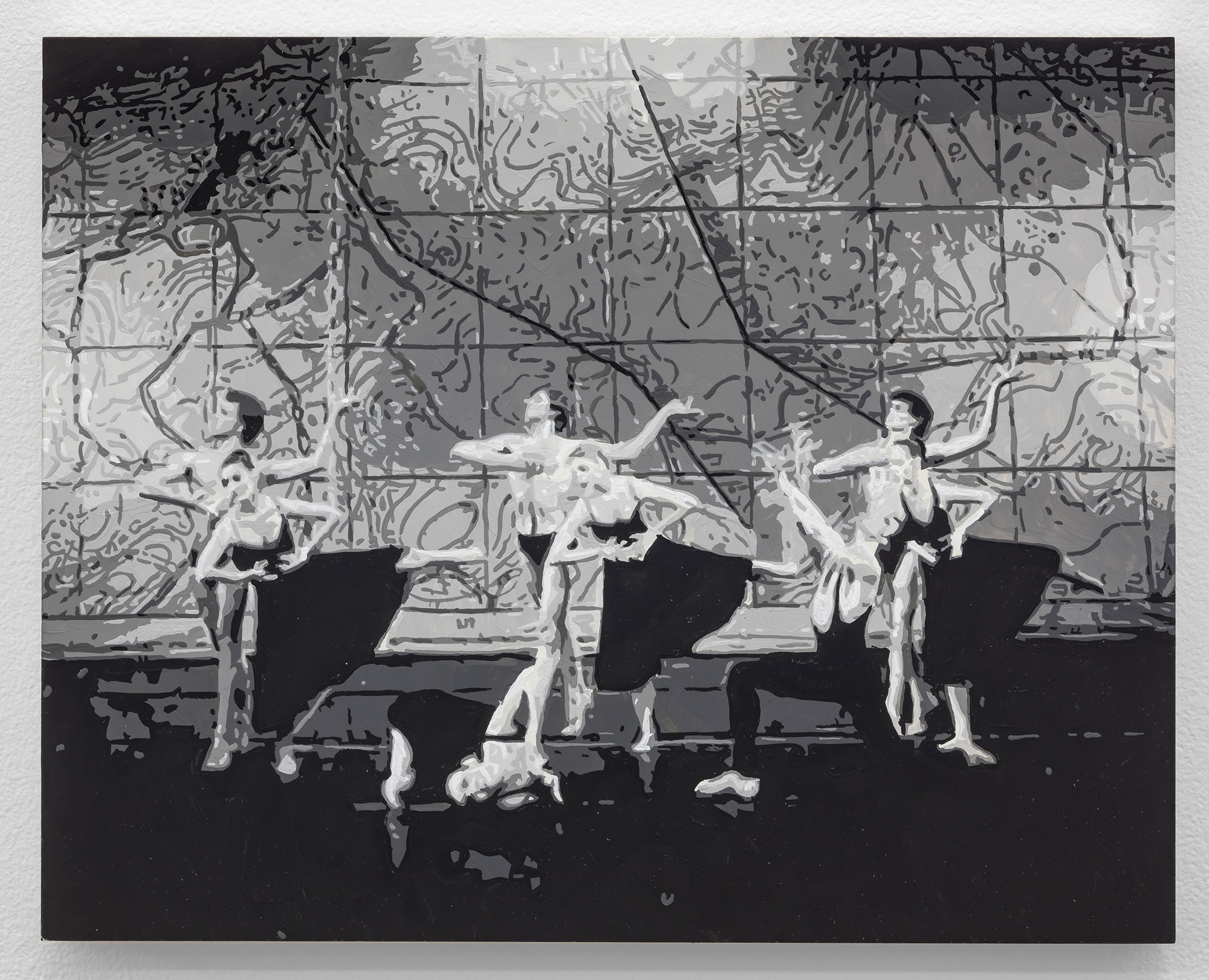

A series of small black and white scenes round out the exhibition. Bat-Dor Dance Company, Joyce Theatre, New York, 1983 shows a performance by the Israeli dance company founded by Bethsabée de Rothschild. Bethsabée, who assumed the name Batsheva after moving to Israel, was born in 1914 in London and educated in Paris. She was the daughter of the Baron and Baroness Edouard and Alice de Rothschild, and the great-granddaughter of James Mayer de Rothschild. The family, who once owned the largest private fortune in the world, unsurprisingly developed a lack of awe for the powerful and important. A pompous aristocrat one day called on Nathan (whose portrait is included in the exhibition) who was head down at his desk. Without looking up, the banker said: "Take a chair." His visitor, affronted, said: "You are speaking to the Prince of Thurn and Taxis." To which Rothschild replied: "Take two chairs."

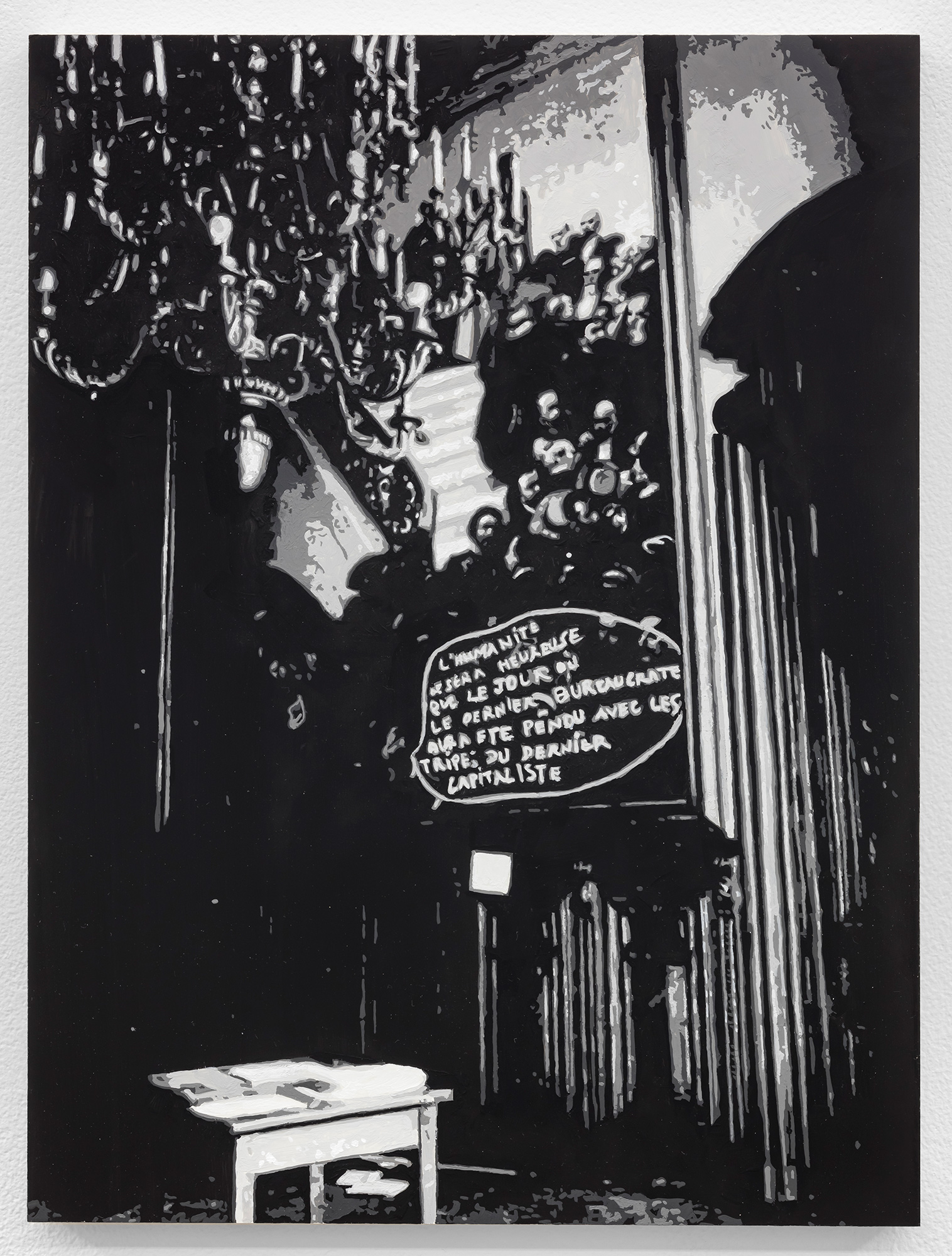

May 13, 1968, Stateroom of the Staircase A, The Sorbonne, Paris is a many-layered work. May of 1968 was the biggest mass upheaval in the history of France and the concurrent wildcat general strike was the most important strike in the history of the European workers movement since World War Two. On May 13, after a demonstration attended by one million people, an open Sorbonne was converted into a stage for assembly democracy, where all questions were supposed to be debated, and passionately were. Later that same day the words “humanity will not be happy until the day when the last bureaucrat is hung with the guts of the last capitalist”, was painted on one of the big frescoes adorning the walls, which caused a scandal. Arguments erupted between preservationists who wanted them protected and radicals from the Sorbonne Occupation Committee who wished to use them for their slogans, and eventually the text was removed with turpentine. The text in question paraphrased an epigram by Jean Meslier who died in 1729. Meslier became a French Catholic priest to please his parents and performed his duties without complaint for forty years, living like a pauper and donating whatever was left to the poor. Upon his death, however, it was discovered that he had written a 633 page atheist "testament" to his parishioners denouncing organized religion as “but a castle in the air” (like the Forbes balloon), fabricated by the ruling elites. In chapter two he writes of a man who wanted "all the nobles to be hanged and strangled with the guts of the priests.” Meslier admits that the statement may seem crude and shocking, but felt that this is what the priests and nobility deserve, not for reasons of revenge or hatred, but for love of justice and truth.

HMS Kilbride, Milford Haven, 13 January, 1919: on this day the Red Flag was hoisted during a naval mutiny on the ship at Milford Haven. Mutinies in the British Royal Navy are not well documented, and often news of them was purposely suppressed to prevent the sentiment from spreading. In the aftermath of World War One (1914-1918) sailors became reluctant to fight Russia after the British government had already pledged to a policy of peace. At the same time agitation for trade union representation was spreading throughout the Navy. The material conditions of the sailors was indeed grim. Between 1852 and 1917 there had only been one pay increase, of a penny a day, in 1912. Another two pence was granted in 1917. After a series of mutinies like on the Kilbride, pay increases of over two hundred percent were finally granted. The ship is also notable for its dazzle paint treatment. Edward Wadsworth was born in 1889, the son of a wealthy textile manufacturer who wished for his son to take over the business. Instead Wadsworth decided to become an artist. He studied drawing, painting, and woodcut printmaking at the Knirr School in Munich and later at the Slade in London in 1909. He became close to Wyndham Lewis who was on a mission in 1914 to birth a creative movement for which he could be its leader. From this zeal came the Rebel Art Centre (an apartment) where its members, including Wadsworth, could show their paintings, and from which rooms erupted “Blast,” a red-blooded manifesto of what Lewis had decided to call Vorticism, “from which and through which, and into which, ideas are constantly rushing” (as Ezra Pound said in his essay, Vortex, in the inaugural issue). But the onset of war soon gravely wounded the movement, inhaling many of the artists, including Wadsworth, who was stationed at the naval yards in Liverpool. Another artist turned naval officer was Norman Wilkinson, a formerly academic marine painter. As the commander of a patrol boat in the submarine infested English Channel he soon hit upon the idea of optically distorting the shape of the vessels with paint to frustrate a correct reading of the size, the distance and the direction of ships when seen through a periscope at water level. Wilkinson convinced the Admiralty and it was Wadsworth, already keenly aware of the high contrast involved with making woodcuts, who eventually oversaw the painting of 2,000 ships.

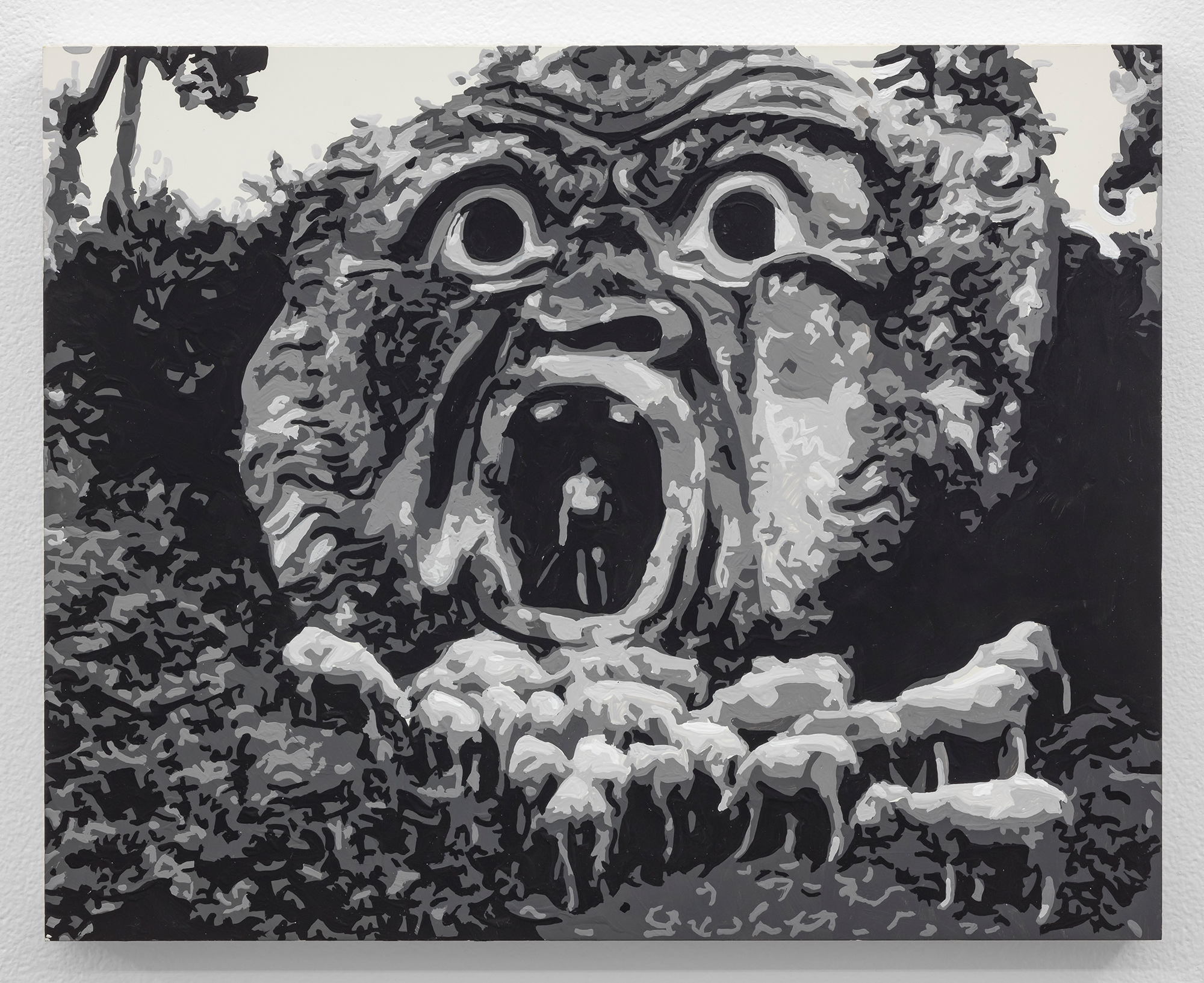

Mouth of Orcus, Sacro Bosco:

The Sacro Bosco (“sacred wood”) is a 16th Italian garden populated by grotesque sculptures near Bomzaro, itself originally a fiefdom of the Orsini, a powerful Roman family (at least five popes belonged to this family). The garden was conceived in 1552 by Pier Francesco Orsini, known as Vicino. He had inherited the duchy of Bomarzo seven years after the death of his father, thanks to the intercession of cardinal Alessandro Farnese (the future Pope Paul III). Vicino was a leader in the pope’s army, fought in brutal wars and was held prisoner for three years. Upon his release he retired to Bomarzo where he devoted himself to his garden and to an Epicurean style of life, which negated any contact with religion. Edmund Wilson called the garden “a kind of malignant poem created by a determinedly perverse nature, which still speaks through its threatening inscriptions and petrified but animated dreams.” Orcus was a god of the underworld, punisher of broken oaths in Italic and Roman mythology. Here the mouth is wide open and on whose upper lip it is inscribed "All Thoughts Fly". There is also a dining table inside the orfice. Dr. Luke Morgan has posited that the "ordinary Renaissance person encountering this ‘Mouth of Hell’ in the mid-16th century might have laughed at the witticism but also experienced a kind of terrifying chill. As Christians who hadn't seen the separation of church and state,” he says, “they would have been frightened to confront the consequences of sin like this and to eat from a table positioned inside a mouth that had you, in effect, participating in your own [hellbound] consumption.” In 1962, the Argentine writer and art critic Manuel Mujica Láinez adapted his novel, Bomzaro, into an opera which had its premiere in Washington in 1967 after having been banned in Argentina for its suggestiveness. In Scene 1, Vicino the Duke goes to the Mouth of Hell with his astrologer and there they find a poor shepherd boy singing that he would not change places with the Duke because the Duke went through life dragging the burden of his sins. Vicino “remembers thinking that everything I had done was worthless compared to the peace of that innocent soul."

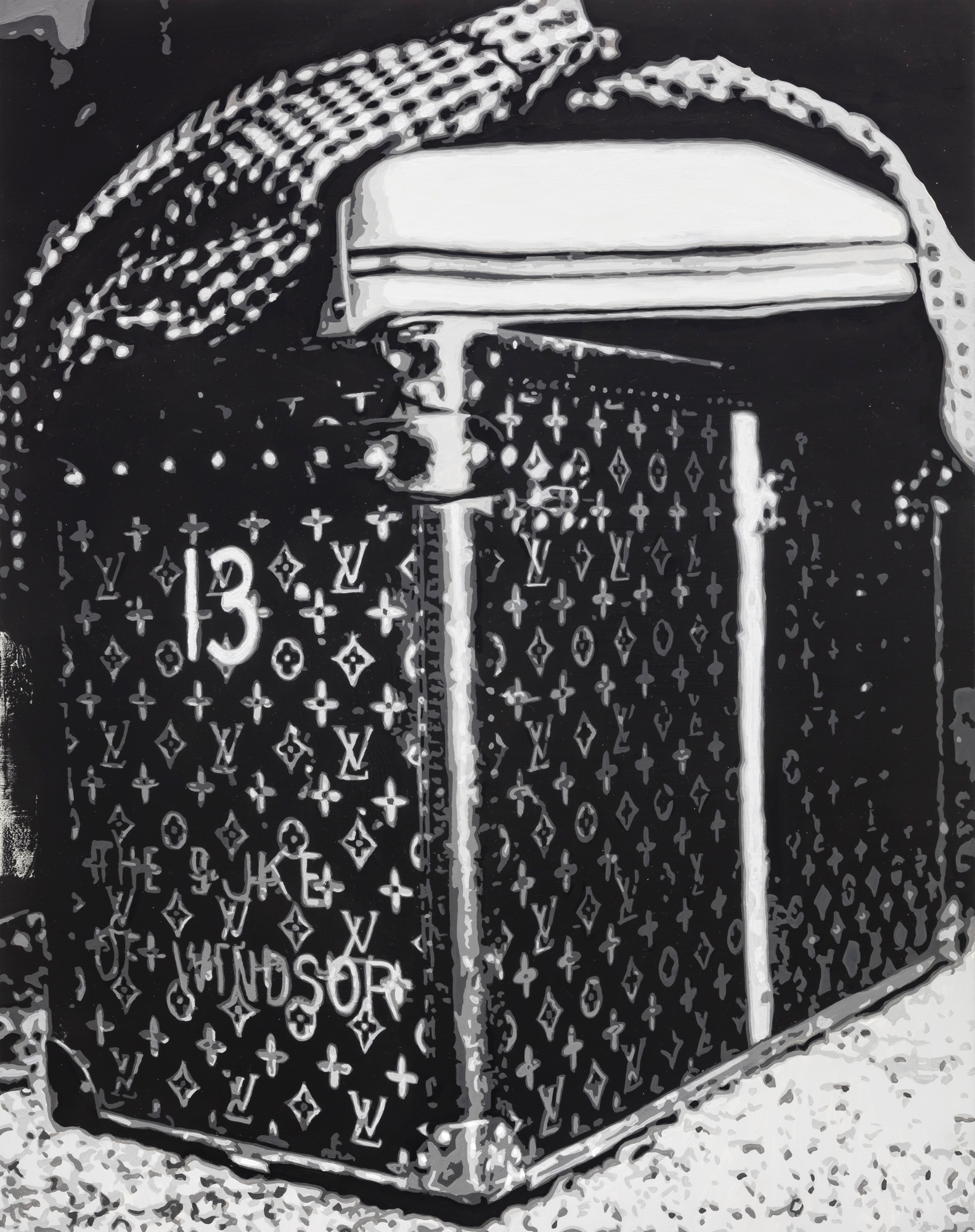

Luggage Trunk, Edward VIII, Duke of Windsor

Edward VIII was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Empire, and Emperor of India, until his abdication on 11 December, after which he became the Duke of Windsor. The only British sovereign to abdicate voluntarily, Edward stepped down in order to marry the twice-divorced American Wallis Simpson. He was king for less than a year. The following day, after broadcasting to the nation and the empire to explain his actions, he left for Austria. The couple settled in France where he supplemented his tax-free allowance from his brother with illegal currency trading. The City of Paris had provided him with a house and they were able to buy goods duty-free through the British Embassy. In October 1937, the Duke and Duchess travelled to Nazi Germany, against the advice of the British government, where they were entertained by Hermann Goering and received by Adolf Hitler at his Berghof retreat in Bavaria (two hours east of King Ludwig’s Linderhof castle...). The visit was much publicized by the German media. During the visit the Duke reportedly gave full Nazi salutes. In Germany, "they were treated like royalty ... members of the aristocracy would bow and curtsy towards her, and she was treated with all the dignity and status that the duke always wanted," according to royal biographer Andrew Morton. Many historians have suggested that Hitler was prepared to reinstate Edward as king in the hope of establishing a fascist Britain. It is widely believed that the Duke and Duchess sympathized with fascism before and during the Second World War, and were forced by Winston Churchill to move to the Bahamas to become its Governor and, primarily, to minimize their opportunities to act on their pro-Nazi feelings.

The Maze, Armand G. Erpf Estate, Arkville, New York

Armand Grover Erpf was a trustee of the Whitney Museum of American Art, an art collector, a senior partner in the investment firm of Loeb, Rhoades & Co., and at the time of his death in 1971 the financial saviour of New York Magazine. He lived at 820 Fifth Avenue and kept a 500 acre estate in the Catskills. Erpf had read a book by Michael Ayrton, an English sculptor and authority on mazes, called “The Maze Maker,” a fictional autobiography of Daedalus and his labyrinth. In the ancient Greek myth, King Minos has Daedulus build a nearly impenetrable labyrinth at Knossos to contain the Minotaur, a monstrous half-man, half-bull. The Minotaur was the offspring of Minos’s wife’s tryst with a white bull that had been given to Minos by Poseidon to offer as sacrifice; instead Minos kept it for himself so in revenge Poseidon, with the help of Aphrodite, made Pasiphaë, Minos’s wife, lust after the bull. King Minos then had Daedalus and his other son Icarus imprisoned in a tower to prevent his knowledge of the labyrinth spreading to the public. Erpf called Ayrton and said “I just read your book. I want one of those.” Michael Ayrton had spent much of his career circling Daedalus’s mythological labyrinth. By the mid 1960s he had written, painted, sculpted, and sketched the labyrinth numerous times, culminating in the commission from Erpf to build the Arkville Maze. It contains 1,680 feet of passageway inside brick walls that range in height from six to eight feet. Two bronze sculptures, one of Daedulus and the other of the Minotaur, anchor the centre. Erpf was said to have considered the maze “an aesthetic experience, a symbol in a world so caught up with scientific rationalism it doesn't know where it's going. You can't get to the centre of a maze by going straight for it. You have to be indirect. The way to attain something is to go away from it. The maze is a spiritual truth.”

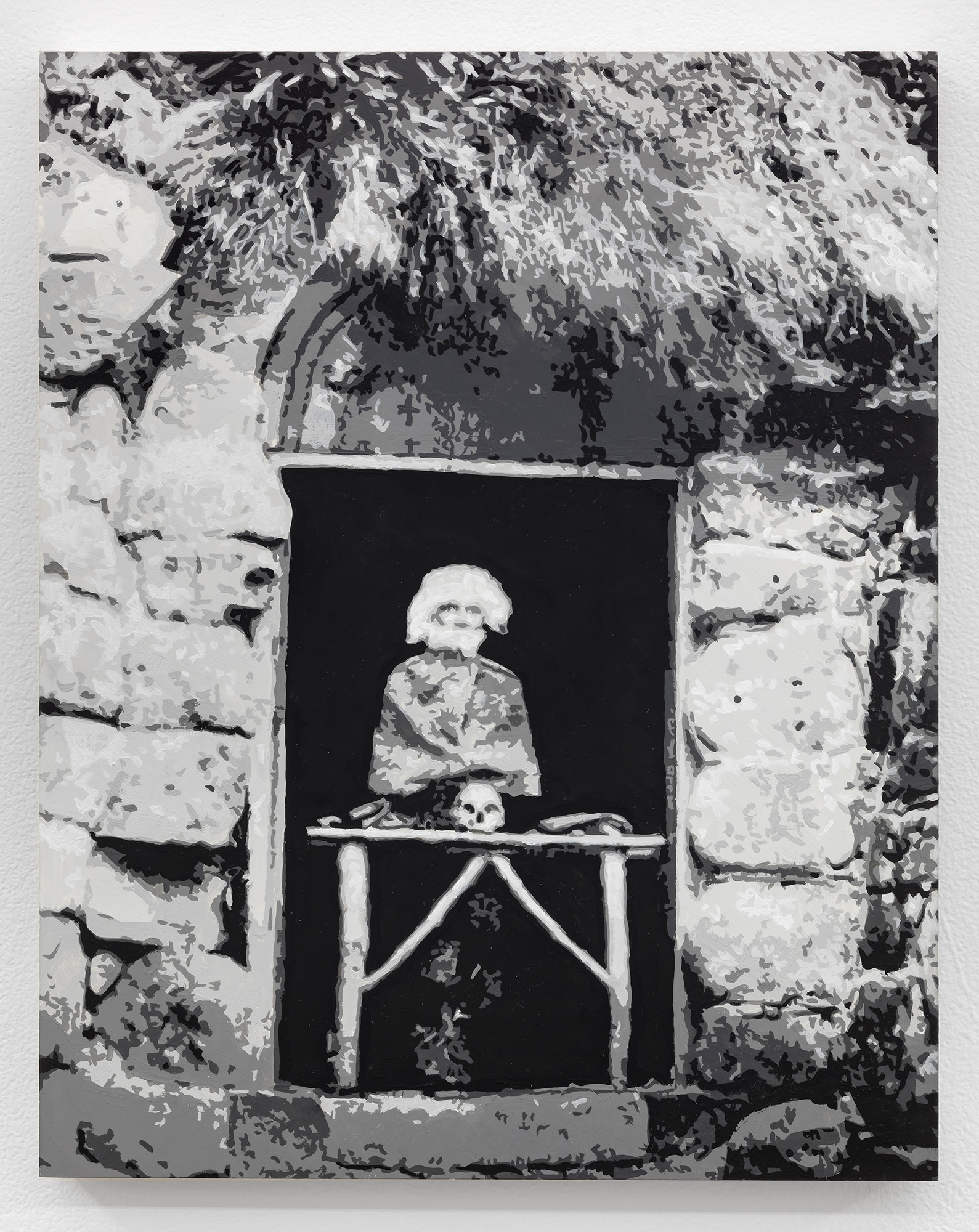

Hermit, Hawkstone Estate, Shropshire

Richard Hill of Hawkstone, known as ‘The Great Hill,’ used the fortune he made from ‘lucrative arithmetik,’ to raise the family into the aristocracy. He inherited Hawkstone Hall, the family seat in Shropshire, in 1700 and his nephew and heir, Sir Rowland Hill, 1st Baronet Hill of Hawkstone, set about expanding the estate and managing its landscaping. It became highly fashionable among the wealthy landowners of 18th century England to commission architectural follies and faux ruins, including the odd hermitage. The logical next step, must-have accessory was the ornamental hermit to animate it. These were men, usually agricultural workers, hired for the sole purpose of inhabiting a small, rough structure and functioning like any other garden ornament for the delight of the owners and their friends. The go to look was Antiquarian Druid. The elite had a fondness for melancholy and introspection, especially when it could be farmed out to others, and the role of their hermit was to embody this. A prized specimen would be “hoary as Job and meagre as a cabbage-stalk” but recruiting one was tricky. True hermits, who shunned society and lived in isolation to pursue spiritual enlightenment, were never thick on the ground in Britain, and would presumably have been too troublesome to deal with anyway. After a landscape designer to Lady Croom had suggested an ad in a newspaper to find one, she replied “but surely a hermit who takes a newspaper is not a hermit in whom one can have complete confidence.” Ornamental hermits, already unclipped and gaunt, would sometimes also be required to dispense spiritual wisdom and provide counsel to the owner’s guests. A 1784 guide to Hawkstone estate describes its resident hermit: “You pull a bell, and gain admittance. The hermit is generally in a sitting posture, with a table before him, on which is a skull, the emblem of mortality, an hour-glass, a book and a pair of spectacles. The venerable bare-footed Father, whose name is Francis (if awake) always rises up at the approach of strangers. He seems about 90 years of age, yet has all his sense to admiration. He is tolerably conversant, and far from being unpolite.”

-

Dorian FitzGerald was born in Toronto in 1975 where he lives and works. He holds a BA in Art and Art History from the University of Toronto and Sheridan College. His work has been exhibited at the Art Gallery of Hamilton, the Blackwood Gallery, University of Toronto Mississauga; the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts; the Galerie de L’Université du Québec à Montréal and the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art (now MoCA), Toronto, among others. His work is held in several public and private collections including the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, the Ivey School of Business and the Donald Sobey Collection. FitzGerald wishes to thank the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council for their support.