Y.M.N.W.T.B.Y.M

Micah Wood

May 4 – June 2 2019

@

Cassandra Cassandra

348 Ryding Ave., Unit 103.

Toronto, ON

— What does “Y.M.N.W.T.B.Y.M.” stand for?

— It is an acronym from the dice game Cosmic Wimpout, short for “You May Not Want To But You Must.” It’s a rule that stipulates when a player has scored on all five dice, normally they could stop, play it safe, and not roll again, but if you score on all five dice, you have to roll the dice again, increasing your chances of losing all of your points in that turn but also increasing your chances of scoring many, many points.

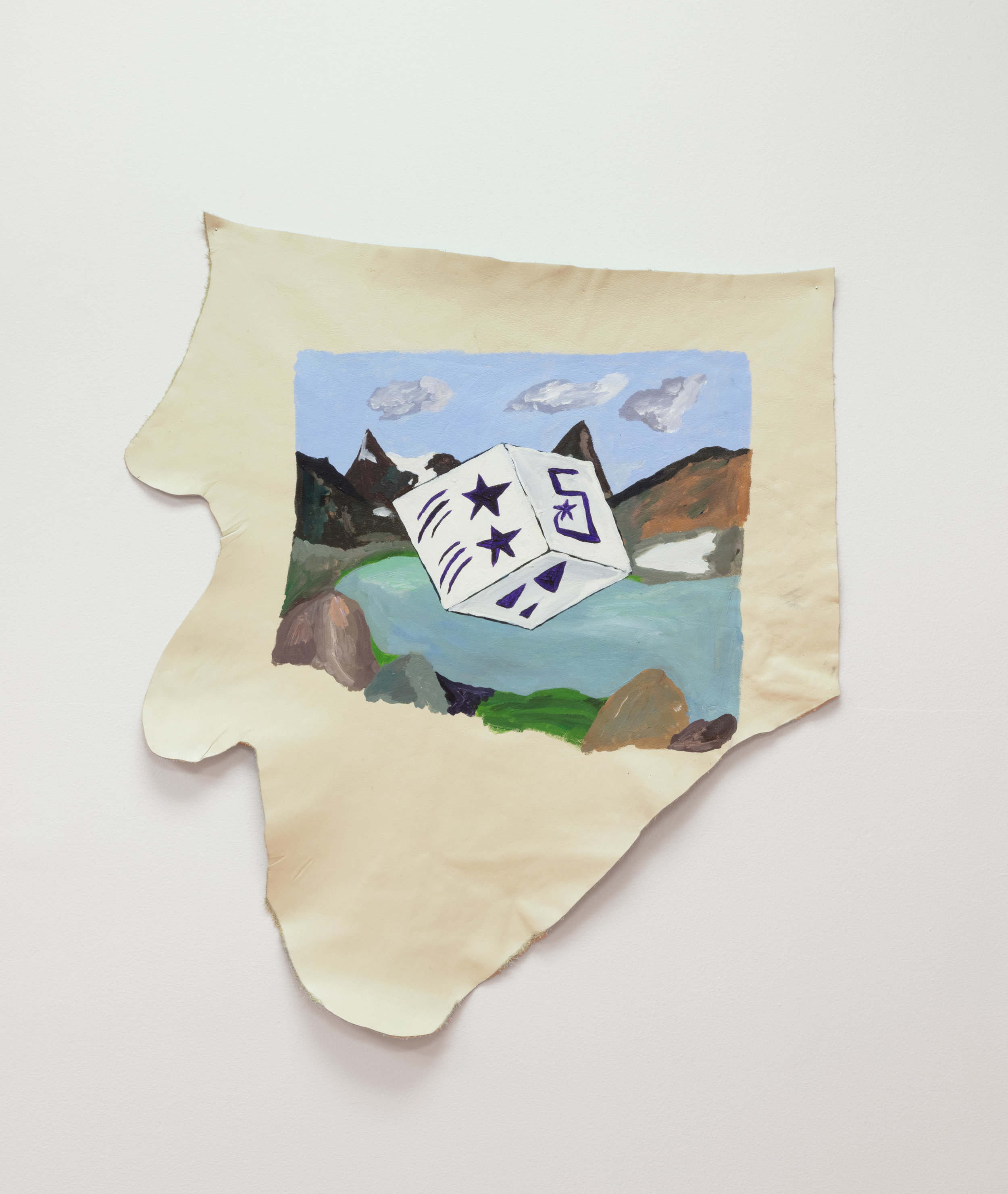

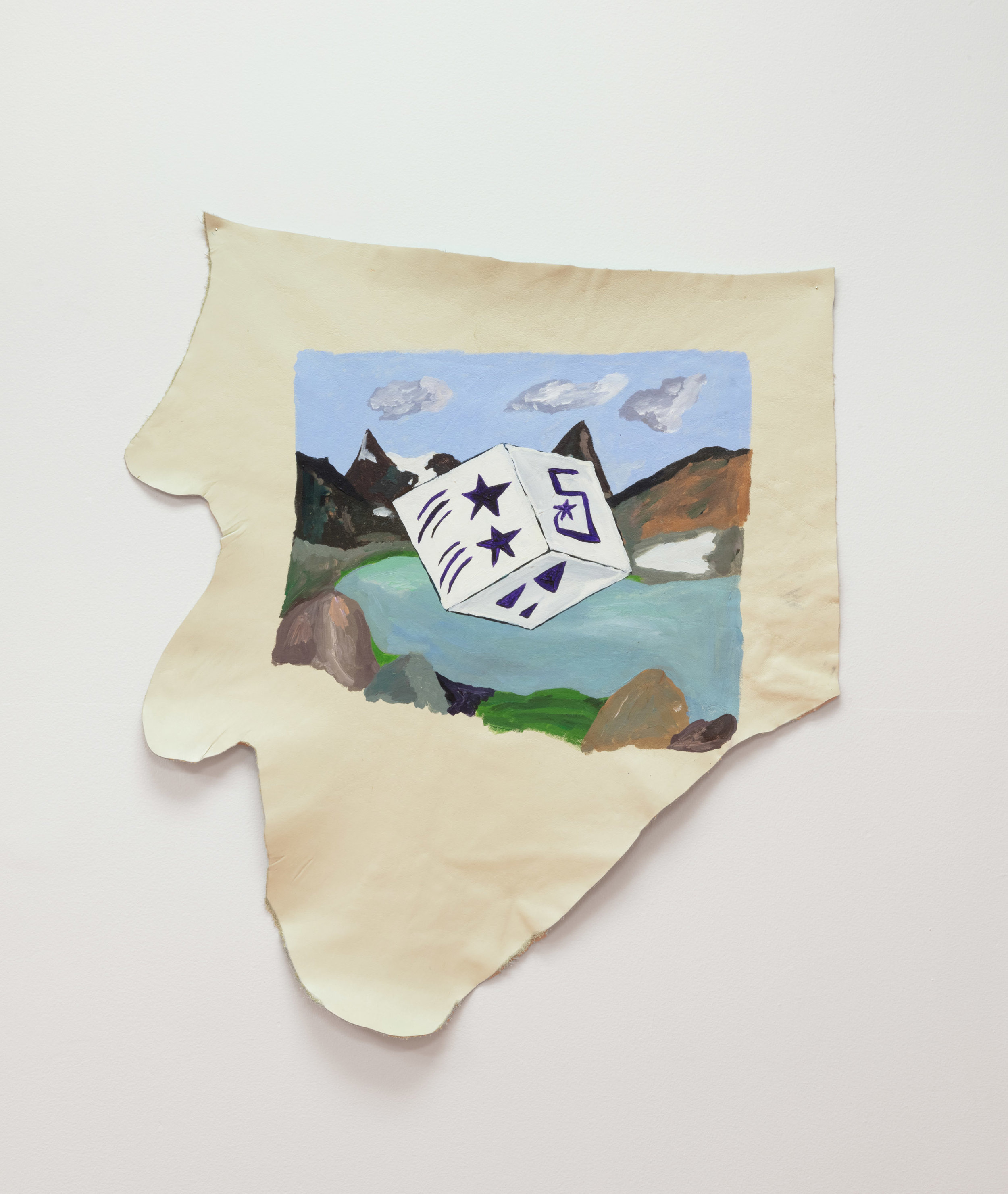

Cosmic Wimpout is a dice game produced by C3, Inc. in 1976. The game is played with five custom dice. Sometimes players use a piece of cloth or felt available in various colors and designs as a type of game board.

— What appeals to you about this game?

— The game is very much about chance. I am interested in the history of the game, and in the subcultures that it exists in, for example, in Berkeley, California, and the Grateful Dead. Many Grateful Dead fans became believers in the game of Wimpout. “Cosmic” means of or relating to the cosmos but it also means relating to the universe and the natural processes that happen in it. This dice game can be played anywhere, in a field of flowers, underneath a starry sky, out in the desert, et cetera. The location in which Cosmic Wimpout is played is arbitrary, it can be played anywhere, it democratizes locality. I also love the design of the game, the new-age style symbols on the dice. Cosmic Wimpout allows people to simultaneously push their luck while also letting people play it safe. In times like these, who can really play it safe?

— Chance is an important element in your practice. Can you tell us more about it?

— When talking about “chance,” I am talking about taking one thing out of context and placing it into another context. Interpretation is determined by site, so if we change the site then the interpretation or meaning is now rearranged, or unfixed. The outcome? Free association. What does this dice game mean in different locations? Chance, will power, karma, it’s in the cosmos. There is common ground between Dada art, experience, and Cosmic Wimpout.

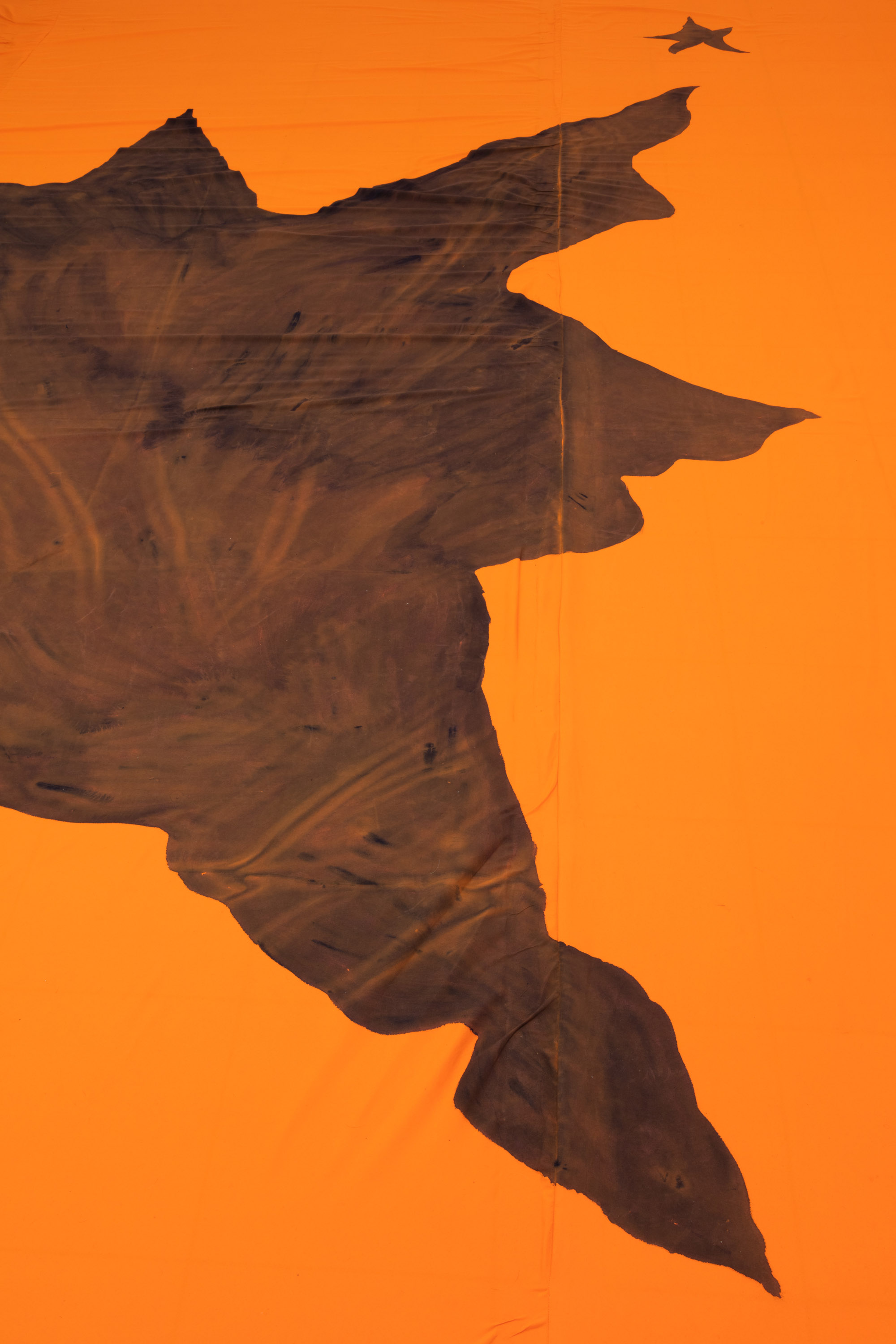

— It’s interesting that you refer to the nomadic aspect of the game. The works in the show are made of leather and polyester, soft materials that allow a certain flexibility. Can we talk about the material’s impact on your work?

— These are new paintings on leather. I feel painting on leather is closer to working on paper than canvas. I’ve been thinking a lot about artificial stimuli and affect display (if objects can have an affective display), verbal and non verbal ways of communication, how certain objects have their own ontology, and the concept of “being distracted” as a general way to make work. I haven’t cleaned

up the edges of the leather, I like the way they are. Leather as a skin carries a lot, but I feel that the leather as a material is culturally so far removed from the animal, maybe that’s more what I mean than artificial, it is this cultural signifier for so many things, that a painting on leather, to me, seems like a hyperreal way to make a picture, because it is so far removed from the source.

— Hyperreality is definitely an important concept in your practice. This idea of fruitful distraction reminds us of the “Theory of the Dérive” by Guy Debord. He defines the Dérive as “a mode of experimental behavior linked to the conditions of urban society: a technique of rapid passage through varied ambiances.” It is an unplanned journey or wandering through a landscape, usually urban, in which participants drop their everyday relations and “let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there.”

But let’s come back to chance! You have dealt with other explorations of chance in your practice like collaborating on the writing of a text as if you were playing exquisite corpse, for example. We also know you are fascinated by the attempt to control cause and effect over chance.

— Chance and the loss of control in concert with the attempt to control cause and effect is something I think about all of the time. Cosmic Wimpout is all about chance and these paintings are what happens when I lose control over the “then/there” mentality I often have.

I was inspired by postcards of landscapes that you can find at a gas station and by artists like Fischli and Weiss. Their sensibility towards materials and the connection between ideas in relation to material is very inspiration for me, in particular, in a piece by them called The Way Things Go (1987).

— The dice are recurring symbols in the compositions, referents of chance. You also depict a variety of landscapes in the background. Are they inner landscapes? How do they dialogue with the dice throws upon them?

— I have been thinking a lot about landscapes as just pure backdrops and contrasting them with something utterly not of the landscape. I think that is more real than the rosemary growing in the garden. I see playing dice as operating an anti-capitalist machine. Chance is the enemy of certainty, and certainty equals capital. Playing dice challenges ideas about who wins and who loses, and Cosmic Wimpout erases ideas about who capitalist winners and losers are. Instead, it gives everyone an equal playing ground from inside the game.

— Earlier you mentioned Dada art. Many Dada artists were critical of the dominant social structures and political strategies that led to World War I. To critique the systems that shaped society, they turned to new art-making strategies. In their attack on rationality, Dada artists embraced chance, accident, and improvisation. Such forces figured prominently in their creation of collages, assemblages, and photomontages—and subverted elements that had long defined artistic practice, like craft, control, and intentionality. It was a form of personal protest and a tool for critiquing the increasingly mechanized, violent world in which they lived. Do you feel like you are creating in reaction to the world today or to something more specific?

— These paintings do feel like a type of reaction, but a response that is maybe more general than specific. In this particular instance I reacted against a mechanized world, and I see chance as an anti- capitalist way of playing by the rules. Something happens or it doesn’t, capital can’t change it. Chance really makes me think of this concept of being distracted. Distraction is an exercise to be used when wanting to create a certain type of painting. When I talk about making distraction paintings, in part it comes from reading about the writings of Guy Claxton, who talks about the “tortoise mind,” a mind where daydreaming and leisurely, contemplative thinking happens, as opposed to the hyper acute, fast “rabbit brain.” I let myself become distracted and look for a web of meaning.

Micah Wood (b. 1988, Bedford, Iowa) received his Master of Fine Arts from California College of the Arts, San Francisco, CA in 2015. He works in a variety of media including painting, sculpture and performance. The imagery found throughout Wood’s paintings oscillates between found images, advertising, and automatic drawing. His paintings are informed by many different sources, from his automatic drawing process to Rube Goldberg machines and fringe theories. Recent solo and group exhibitions include Simultanhalle, Moscow Museum of Modern Art (Moscow, Russia), Héctor Escandon (Mexico CIty, Mexico), Johansson Projects (Oakland, CA), Egyptian Arts and Antiques (Los Angeles, CA), and the Fondation Des Etats-Unis (Paris, France). He was a co-director of City Limits Gallery in Oakland, CA from 2016-2018 where he organized several solo and group exhibitions. Wood lives and works in Los Angeles, CA, USA