Points of Light

Hito Steyerl, Jean-Luc Godard, Gary Hill, Angelica Mesiti, Christian Marclay

@

Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal (MAC)

By Uriah Marc Todoroff

A pulsing, early-Internet techno rhythm draws me into a big empty room, where the iconic wave structure of Hito Steyerl’s Liquidity, Inc. has been installed at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal (MAC). Steyerl’s piece is on display as part of the Points of Light exhibition, a six work exhibition “attesting to the range and depth of the Musée’s video collection,” alongside works by Jean-Luc Godard, Angelica Mesiti, Christian Marclay, Gary Hill, and Nelson Henricks. Points of Light charts the historical development of video art and the philosophy at its heart. The exhibition was originally scheduled to run until 14 June 2020, and is now cancelled because of the pandemic.

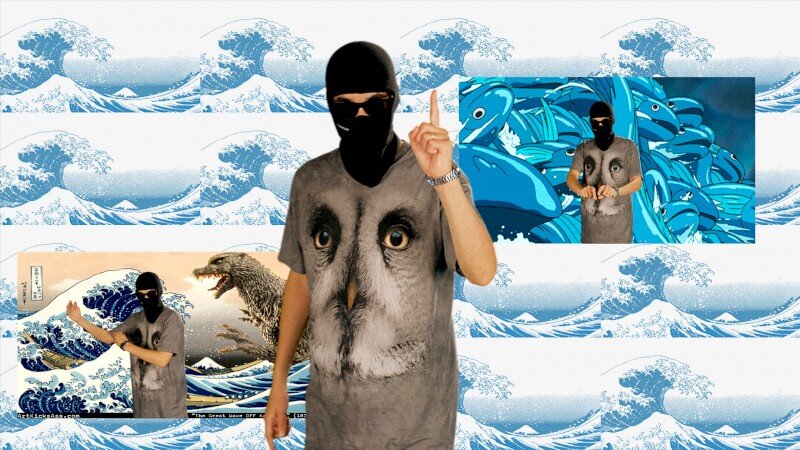

Hito Steyerl, Liquidity Inc., 2014, Single-channel HD video, colour, sound, 30 min and architectural structure, 1/7 257 x 450 x 40 cm (architectural structure), Musée d'art contemporain de Montréal. Photo by Paul Litherland.

Hito Steyerl, international artist, philosopher, and prolific writer, is known for working and theorizing primarily in video and installation. She deals with questions of data, surveillance, digital images and the relationship between image production and military and social institutions. The judo mat viewing structure is large enough for at least a few people to sit six feet apart, nestled in the rough-textured rubber crook of the wave. The 30 minute video is projected onto a large screen at the base of the structure, rising as though from out of the sea. The entire piece forms a semi-contained semblance of the cinema, soundtrack booming cavernously through the shadows.

Liquidity Inc. (2014) is an abstract fusion of documentary, atmospheric visuals of digitally rendered waves and storms, and absurd sketch segments that harken back to new forms of algorithmically networked video content. Recurrent symbols include Hokusai’s Mt. Fuji, and screens. “The work is inspired by Jacob Wood, a financial adviser turned MMA commentator,” Steyerl told Laura Poitras in Artforum. Jacob Wood’s journey from working at Lehman Brothers, to working in MMA after the 2008 collapse, is the perfect journey of the neoliberal subject. Bruce Lee’s fighting philosophy to “be like water” is intercut with Jacob’s narrative, connecting the martial liquidity to the liquidity of neoliberal precarity. “Reporters supposedly from the Weather Underground come onstage to announce the weather, but the weather is a strange mixture of man-made weather, political weather, affective weather... There are storms brewing everywhere, different bits and pieces mixed up in one continuous tsunami.”

Steyerl, Liquidity Inc. Image courtesy of KOW Berlin. Accessed 14 May 2020, https://kow-berlin.com/artists/hito-steyerl/liquidity-inc-2014.

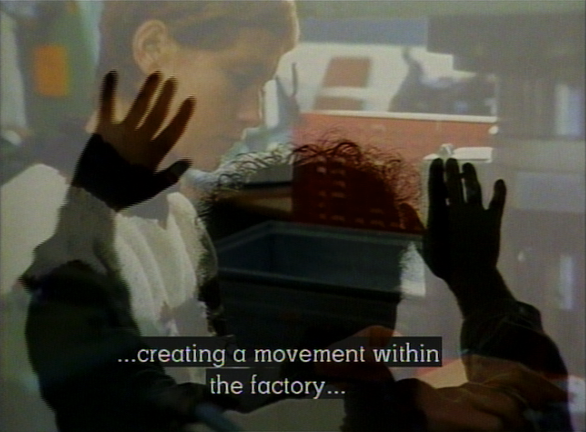

In another room, Jean-Luc Godard’s video documentary from 1982, Scénario du film ’Passion’ is projected opposite Gary Hill’s cinemagraphic double portrait of Isabelle Huppert, Loop Through (2005). Another loosely-formed documentary piece, this film is of a much greater length at 52 minutes. Scénario is based on Godard’s production of a feature film from the same year, Passion. Shot without a script, Passion tells the very minimal story of a young factory worker named Isabelle (also played by Isabelle Huppert) who connects with the director (based on Godard, played by Jerzy Radziwilowicz) of another script-less film, also titled Passion. In this second-order Passion, the camera moves over actors re-enacting in living tableau some of the high points in the Western canon of oil painting. Godard delivers Scénario’s narration into a camera from his editing booth, his signature thin, wild hair, cigarette smoke and sunglasses silhouetted against the blank white of a projection screen. He ruminates in intimate voice-over about the origin and meaning of Passion, its autobiographical elements, the nature of cinema, and the two themes of love and labour.

Jean-Luc Godard, Scénario du film ’Passion’, colour video, sound, 54 min, Musée d'art contemporain de Montréal.

Scénario uses footage from Passion, from Godard’s oeuvre, and from a variety of other sources–including what appears to be behind-the-scenes footage shot by a documentary crew working on set. This footage of people filming that was filmed by Godard presents to us what was, in its original context, fictional, as the documentary content of Scénario. Passion is barely a film, almost more like a documentary of its production: it resembles a film and is easily digestible, but the source from which it draws its content is its own process of making. Form and content in this film are unified around the political critique of Godard’s filmmaking, his “militant cinema.” Scénario’s account of that production method shows how, through the objectivity of experimental form, aesthetics uncovers the reality of social relations.

For the first half of its history, photography bore the indexical truth-stamp of reality; but with electronic imaging technology, the “truth” of a photo can become blurry, or even completely refigured. As Scénario layers footage from different sources within the hierarchy of reality, the images lose their natural ability to tell the truth; they become overlaid, literally blurred, and we return to the booth, and the blank page of the projection screen.

Godard, Jean-Luc, Isabelle Huppert, Hanna Schygulla, Michel Piccoli. Passion, DVD. Directed by Jean-Luc Godard. Paris, Parafrance Films, 1982.

In the three decades that separate Scénario and Liquidity Inc., technologies of image production and circulation have proliferated explosively, giving birth to many new theories of art history. Steyerl navigates the same disciplinary terrain as Godard, but uses the motifs and methods of online culture to critique how digital images have been appropriated by neoliberal social institutions. In Liquidity Inc. we are treated to cheap CGI, crude green screen effects, and a collision of documentary with a form evolved from online content. The soundtrack and every element of the mise-en-scene recall a vision of Internet culture that was dated at the moment of its arrival. Segments of the video reveal the UI of Steyerl’s computer, complete with intruding notifications about mental health, money, and drowning. The affective weather presented by the Weather Underground characters is associated with the screen-images of networked life. The computer screen has taken the place of Godard’s projection screen, a blank page of infinitely compounding digital malleability.

Before its untimely end, Points of Light was constructed around these two centrepieces from celebrity artists, both of whom are famous for their political critique. The stylistic difference between the two is especially pronounced if we compare Passion, relatively typical Godardian fare whose visual lexicon is drawn from art history; and Liquidity Inc., which draws its iconography from an emergent visual tradition. The two works speak to each other from dramatically changed historical conditions. Godard–at least during this period of his career–was a militant Marxist filmmaker; Steyerl is one of our most celebrated critics of neoliberalism. The economic mode which we presently endure represents a paradigm shift from the mid-20th century state capitalism that informed the older filmmaker’s reality, and the material conditions of the two epochs entail different aesthetic responses. Liquidity Inc. is a film about neoliberalism whose dominant theme is the symbolic representation of that economic mode, and which uses historical developments in the condition of photography to critique how that technology has been appropriated by neoliberal institutions. Scénario du film ’Passion’ and Passion are both interested in an older bourgeois reality that perhaps only lingers on in a sham vestige today.

Godard, Passion

Hito Steyerl publishes some of her work in editions, and her 2013 film How Not to be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File is available for free online, but the reader will be hard-pressed to watch Scénario du film ’Passion’ or Liquidity Inc. outside of a gallery. Digital photography completely transcends the analogue relation; images are reduced to a series of bits, allowing them to be reproduced or manipulated at their most elementary level. Some artworks that are caught up in legacy institutions are made to yield surplus value by closely hoarding the artwork’s aura, even when the medium of the work itself wants to be free. “Editing, with newer media and with physical reality becoming mediatized to a large extent, becomes a much more expanded activity…Now instead of expanded cinema, it’s expanded editing, expanded postproduction, and circulation across different platforms and formats. I think it’s one of the crucial lenses through which to analyze contemporary activities.” Despite sensitivity to the political-economic issue of distribution, and the reliability of images, both in her works and in her writing, Steyerl’s works are still ensnared in the aura-hoarding art institution. The political and economic role of online platforms has only become more dire as technology companies consolidate.

Scénario was projected in a corner with only one backless bench for viewers to sit for its nearly feature-length runtime. Despite this, I was glad to see an exhibition that so comprehensively charts the contours of video art; although the majority of the pieces were from the past 20 years, the exhibition picks up on currents that run through the history of the medium. In hindsight, I feel lucky to have caught the show before the culture industry inevitably and unforeseeably changes because of the pandemic. Aesthetic investigations into the nature of electronic imaging, and critique of how the neoliberal order has benefited from those images at our expense, are still pressingly important. Perhaps of greater importance today is a critique of how art institutions exhibit these works, as their desperate clutch on a work’s aura feels highly anachronistic in a world gone almost entirely digital.

Uriah Marc Todoroff is a communist writer and art critic based out of Montreal. His writing has appeared in The New Inquiry, The Platypus Review, and on his personal blog at https://umt.world. Follow him on twitter @theinvertedform.