Garrett Lockhart

Wrought Bundle

March 18 - April 25, 2021

@

Afternoon Projects

Vancouver, Canada

Review by Leo Cocar

Since I was a kid, me, and everyone I love has been haunted by the looming “big one”. That term, bracketed in heavy scare quotes, probably calls up something different depending on the geo-temporal context, but for me, a Vancouver boy through and through, “the big one” is an inevitable cataclysmic event in which the Juan de Fuca strait slips an inch too far, Richmond sinks into the ocean and everything goes to shit. The funny thing is that for most, this seismic event is conceptualized as one, singular, apocalyptic moment, a break from the geological reality that the Juan de Fuca strait is in a constant state of tectonic movement, and that microscopic “big ones” are part and parcel of the reality of us living on British Columbia’s coast. Everyday there is slippage, a movement underneath our feet, that despite our inability to perceive, is present all the same.

Wrought Bundle, a solo exhibition by Garrett Lockhart at Afternoon Projects in Vancouver, British Columbia Canada, is a collection of multimedia works, sculptural objects, and assemblages working off of this moment of disaster, an event that is allegedly bound to happen but within a time-span yet to be determined. The exhibition presents viewers with theoretical “survival packs”, bundles of objects meant to help navigate a possible massive seismic event. The sort of beauty in the show is that it operates conceptually on both a micro and macro level - that is, Garrett presents a framework in which to think about time and events on a larger scale through objects that are laden with subjectivity and personal mythologies. Wrought Bundle’s conceptualization of time lies somewhere in between the Buddhist idea of impermanence - anitya - and specious time, that temporal space which is immediately sensed, and rooted in the present. Instead, Garrett’s work invites us to take stock of the smaller moments, even the imperceptible ones, as a way of imagining the future. Although the end isn’t necessarily nigh, we can still prepare, or imagine a futurity all the same.

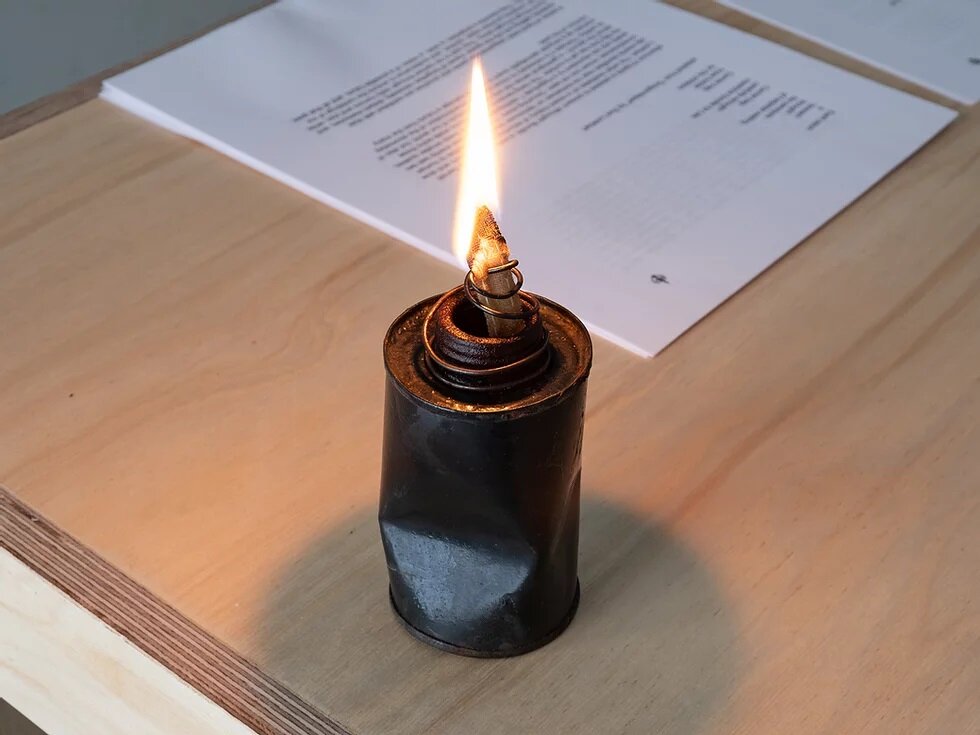

Many of the works are made with found objects, which communicate a sense of place, or by incorporating gestures and materials gathered from loved ones, all the while thinking of the future in a myriad of ways. Works like Bag, Water Pack, and Heater offer visions of the future, potential tools that would account for our basic needs - heat, water, food etc. These works function as sort of counterpoints to other objects that account for more mundane needs. Line Dry, which takes the form of a pair of mended wool socks strung up on a clothesline caked with clay from North Vancouver offers an illustration of the day-to-day that would no doubt exist even in the worst hellfire: laundry, taking care of one’s things, fixing stains and holes. A mobile studio and office, Desk with a View, is a potential piece of furniture or architecture fashioned out of a found, overturned plastic bin. Replete with a notebook, pencil, playing cards, and the acclaimed mycological guide All that the Rain Promises and More (1991), it is a funny visualization of a studio practice at the end of the world. A number of the works themselves are (at least partially) the products of small “big ones” or miniature disasters. Untitled (Bottega Bootleg), a post-apocalyptic ode to people’s need for luxury, is hung on a nail pulled from a flat tire. Untitled (lamp) and Desk with a View use materials found at a burned cabin, further figuring ways in which we can think of the future in response to different disaster scenarios.

Bag, an assemblage of objects contained within a heavily reconstructed 1970s mailbag - a nod towards the artist and the artist’s father’s employment history- acts as a storage device for various tools and materials for survival. Whether these tools would actually allow us to escape a Vancouver-in-Flames is up for debate, but aesthetically, Bag would look just as home in a Mad Max movie or in the Gulf Islands. Among the various tools and materials inside, is a pair of well-worn Birkenstocks, which is almost sickeningly British Columbian but in the best possible way, an analog for Garrett’s practice that undeniably bears the artist’s presence, like a decade old cork sole. Like a nesting doll, Bag contains four untitled works, which are themselves smaller survival bundles, one of which contains a poem by Lockhart’s grandmother. This last element is why I kept coming back to Bag. It's reminiscent of the earthquake survival packs we’d make in elementary school, always packed with objects to aid in our physical survival while always making sure to contain a momento of our family, a spiritual fulfillment.

Wrought Bundle does away with the sort of cold indifference often found in other assemblage or readymade art practices. Talking to Garrett about the show, he said that a friend described it as “twee”, but not in a derogatory way (until I heard this I thought calling something twee was inherently trash talk), and I would agree. The human experience isn’t only a set of material needs, but inherently requires a social and emotional dimension. Even at the end of the world, we’ll need poetry.

Lockhart’s show occupies two spaces at the same time, offering a universally applicable vision of time and future while remaining intensely personal. Although the idea of the “big one” in Wrought Bundle points to a specific geological event, in reality, everyone’s apocalypse looks a little different, and it's in a constant state of unfolding. The “big one” for Garrett won’t be the same for me, nor for you and it certainly won’t be concentrated into a single moment. Armageddon isn’t a bang, it's a slow burn.